Written by Gregory Carr, Ph.D. is Associate Professor and Chair of Howard University’s Department of Afro American Studies for Ebony Magazine – January 6, 2016

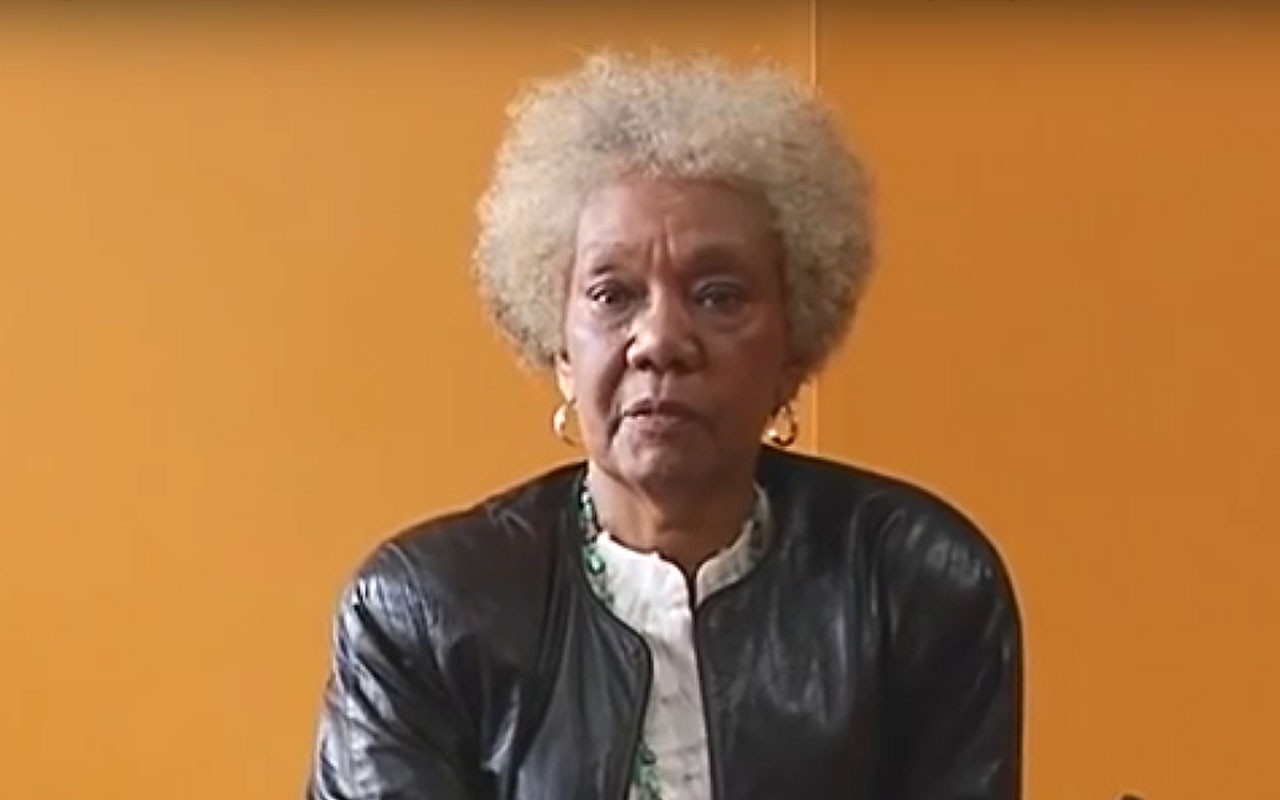

For those unfamiliar with the name Dr. Frances Cress Welsing, who passed away on Sunday at the age of 80 in Washington D.C., she was one our country’s most influential and controversial theoreticians on the subject of race and racism. Her influence did not stem from citations in academic journals, although she gained major recognition after publishing her groundbreaking 1970 essay, “Cress Theory of Color Confrontation (White Supremacy),” which began as a paper presented before members of the American Psychological Association.

Her analysis of the impact of White supremacy was trenchant, hard-hitting and consistent. But like other scholars and “activists” in the Black community who knew Welsing and studied her work, I saw her as an unswerving champion for African Americans and lover of humanity.

Born in Chicago to a physician and an educator, Welsing was trained in the liberal arts at Antioch College and in medicine at Howard University College of Medicine, where she would eventually serve as faculty. A long-standing private practitioner and pioneer in the fields of child psychiatry and mental health, her longest institutional affiliation was as the Clinical Director and Staff Physician with the Washington D.C. Department of Human Services, where she charted policy and strategies to help emotionally disturbed children at the Hillcrest Children’s Center and the Paul Robeson School for Growth and Development.

Welsing’s work on improving the mental health of African Americans led to a career in the field of race and cultural analysis. The Cress Theory was influenced by the ideas of a Washington, DC acquaintance named Neely Fuller, Jr., and explored the thesis that racism, aggression and hostility stems from White fear of genetic annihilation in an overwhelmingly non-White world. Fuller and Welsing contended that all of modern global relations were affected by White supremacist ideology and symbology, which they further grouped into nine categories of human activity: economics, education, entertainment, labor, law, politics, religion, sex and war.

She initiated the development for two generations of popular discourse in Black communities on the concept and reality of White supremacy, a status confirmed by her 1991 book The Isis Papers: Keys to the Colors, which was a collection of essays she had written over the previous two decades. It became a perennial non-fiction best seller in Black communities. Her 1974 debate with the Stanford Nobel Laureate, Dr. William Shockley —a proponent of the idea of Black intellectual inferiority—brought her to national attention. One of two articles she wrote for EBONY that year encouraged Black people to “get very quiet and calm and begin to think critically and analytically in a very broad perspective and cease doing push-button reactions to social events that happen around us and that relate negatively to us.”

In fact, this was Welsing’s consistent call— for Black people to take themselves seriously enough to analyze the system in which they lived and its impact on their lives. She contended that systems, rather than episodic challenges, marked the power of White supremacy over its victims. She came of age in the shadow of Jim Crow; began her professional life during the Black Power era; saw prominence during the post-Civil Rights ideological debates of the 1970s and 80s, and re-ignited new generations searching for direction during the “golden age” of hip hop and the subsequent fracturing and turn of our “post-soul” era. In some ways, her life and work traces the struggle over self and group identity that Black Americans have been embroiled in since the end of legal segregation. She often said that her intellectual guide was W.E.B. Du Bois who accurately observed that the problem of the modern era would be the global problem of the color line and the reaction of non-Whites to it.

The life and labor of Frances Cress Welsing is just one barometer of the gulf that remains between White and non-White public spheres in a society willfully blind to its inability to engage in “honest dialogues on race.” She weaponized her theories with an agenda that most people are afraid to discuss openly and honestly in polite company. She proposed that Black people avoid marriage until age 35 or older because we are not mature enough to raise children to survive and thrive in a White supremacist system. She said Black people should educate their own children and combine their resources to support Black institutions as a first order of business.

The dimensions of her work that critique Whiteness and its cultural impact fit comfortably today within the larger range of what are now called “Whiteness studies” and even elements of “Critical Race Theory.” Even the casual reader of the work of academics and writers like David Roediger, Joe Feagin, Harriet Washington or Peggy McIntosh would find Welsing is not alone in her interrogation of the intersections of race, class, gender, biology and power.SEE ALSO

But, unfortunately, I don’t believe she will be remembered along with those names.

Much of the controversy around Welsing’s ideas on the topic of race comes from an ignorance of the full range of her actual words and ideas. Many of her critics never met her or read little to none of her work. Some of the more informed criticisms mistake her focus on the roots of White supremacist as a belief in and/or call for “Black Supremacy.” That critique forms around her discussion of the biological and social function of melanin, which she consistently said was an object of desire and envy of Whites. Then there were her ideas on sex, primarily her assertion that the gender politics of White patriarchy had promoted homosexuality in Black communities as an attack on the growth and viability of Black families. For Welsing, race, class and gender issues in Black communities traced their roots to the corrosive systemic impact of White Supremacy, at the core of which was patriarchy.

As the life and legacy of Frances Cress Welsing continues to be celebrated and debated, there is no doubt that in the 21st century racism remains an intractable enemy of humanity. In a modern world shaped in the image of Europe and Europeans, no non-White group wants to be, in the language used by Duke University professor and cultural anthropologist, J. Lorand Matory, PhD in “last place.” Ending racism has never been a matter of polite discourse or easy solutions. People will not agree and paths of most resistance will involve fighting with one another. It appears then that the systemic work of racial oppression will continue, unimpeded, until all people of good will determine that it can only end with our collective active participation. Wouldn’t that then be a fitting tribute to an intellectual warrior like Dr. Frances Cress Welsing.

Read the original article at https://www.ebony.com/news/dr-frances-cress-welsing-looking-back-at-her-call-to-uproot-racism-333/.